Housewives Seduced by Seaweed

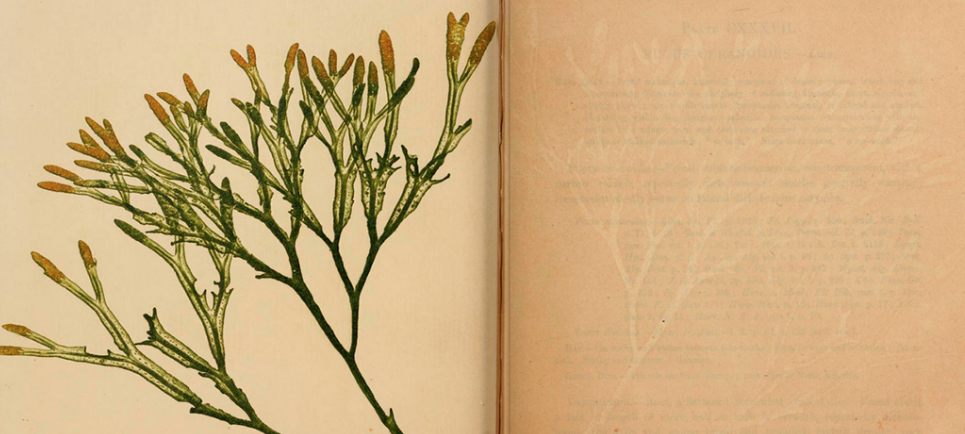

One of Bradbury’s nature prints featured in Johnstone and Croall’s seaweed guide. Developed in 1853, the process created an impression of the plant on a lead plate, which was inked and used to make highly realistic prints.

One of Bradbury’s nature prints featured in Johnstone and Croall’s seaweed guide. Developed in 1853, the process created an impression of the plant on a lead plate, which was inked and used to make highly realistic prints.

Thank you Collector’s Weekly for the repost of the partial article. We highly recommend the book “An Ocean Garden”, which celebrates the beauty of seaweed. View the book here.

“Among quaint fads of the 19th century, like riding bicycles or playing board games, one sticks out like a sore thumb—the Victorian-era obsession with seaweed. That’s right: Affluent Victorians often spent hours painstakingly collecting, drying, and mounting these underwater plants into decorative scrapbooks. Why seaweed?

In Western Europe and the Americas, the 18th and 19th centuries were a time of major cultural upheaval, as industrialization reshaped nearly every aspect of daily life. New national holidays and improved labor laws gave working people more time off, which they could spend at home or enjoy by the seashore, often a quick train ride away. At the same time, influential naturalists like John James Audubon and Charles Darwin helped develop a popular interest in science and nature. Birdwatching boomed; taxidermied creatures filled middle-class homes; fur and feathers dominated fashion trends.”

A collection of seaweed from the Jersey area of the United Kingdom, circa 1850s. Courtesy the Natural History Museum, London.

A collection of seaweed from the Jersey area of the United Kingdom, circa 1850s. Courtesy the Natural History Museum, London.

Two cyanotype prints from Anna Atkins’ “Photographs of British Algae,” released as a series between 1843 and 1850.

Two cyanotype prints from Anna Atkins’ “Photographs of British Algae,” released as a series between 1843 and 1850.

“The shift to wage labor also helped spread the concept of leisure time, when people could explore their personal interests and hobbies. As the Victorian parlor or “withdrawing room” became the focus of private life, the chaotic outside world was ordered and beautified through home furnishings and decorative collections. Finally, improvements in printing technology created an explosion of paper ephemera, like the die-cut imagery explicitly designed for album-making. A generation of scrapbookers was born.

Seaweed collecting embodied a cross-section of Victorian-era pursuits, allowing people to explore nature, improve their scientific knowledge, and create an attractive memento to decorate their homes. By the 1840s, several books on identifying and preserving seaweed had been published, including the series “Photographs of British Algae,” by Anna Atkins. Atkins’ guide is considered the first-ever book of photography, as she used cyanotype prints to document various species (seaweed was placed onto photo-sensitive paper and exposed to light, resulting in a negative image of the plant).

Inspired by the work of Atkins and others, amateurs all across the U.K., Canada, and New England began tramping into tide pools to collect their own specimens. Laura Massey, a cataloguer for rare bookseller Peter Harrington, explains that such scientific pursuits weren’t limited to men; they also represented a respectable pastime for women “who were not expected to study science for its own sake, but as a social accomplishment.

Massey began researching the world of seaweed collecting after her firm acquired a handmade seaweed album marked “Miss Mary Carrington,” though it’s still unclear whether the book was made for or by Ms. Carrington. We recently spoke with Massey about the insatiable curiosity of Victorians and their love of seaweed.

Two cyanotype prints from Anna Atkins’ “Photographs of British Algae,” released as a series between 1843 and 1850.

Collectors Weekly: How did your firm acquire Mary Carrington’s album?

Laura Massey: A colleague and I have a particular interest in women’s history and in craft skills traditionally defined as feminine, and we keep our eyes open for unusual items, such as this album, which we purchased from another bookseller. We think that this example came from the northeastern United States, because the blank book in which the seaweed was arranged was published in New Haven, Connecticut. That location makes sense, as seaweed is plentiful along the cold, rocky shores of New England, and the region would have had a large population of middle- and upper-class young ladies with the time and resources to pursue aesthetic and intellectual hobbies.

This is the first seaweed album we have handled, and they seem to be among the rarer types of albums we come across. There are several reasons for this. Seaweed collecting wasn’t quite as popular as mainstream hobbies—it was more technically demanding than pressing flowers, and was restricted to regions where seaweed occurred naturally, or to people who could travel to those regions.

I also suspect that when families were dealing with estates they might have seen the aesthetic value in an album of fashion prints or flowers, but perhaps not in seaweed, and discarded them more readily. But as with other types of material, these come and go on the market, and you might go a long time between sightings and then stumble across two or three in a short span of time.”

Read the rest of the article on Collectors Weekly.

A nature print by Bradbury, circa 1859.

A nature print by Bradbury, circa 1859.

The album labelled “Miss Mary Carrington” and one of the book’s pressed seaweed samples, circa 1830

The album labelled “Miss Mary Carrington” and one of the book’s pressed seaweed samples, circa 1830

>>Article by Hunter Oatman-Stanford on Collectors Weekly. Buy “An Ocean Garden”, a book which explores the beauty of seaweed, here.