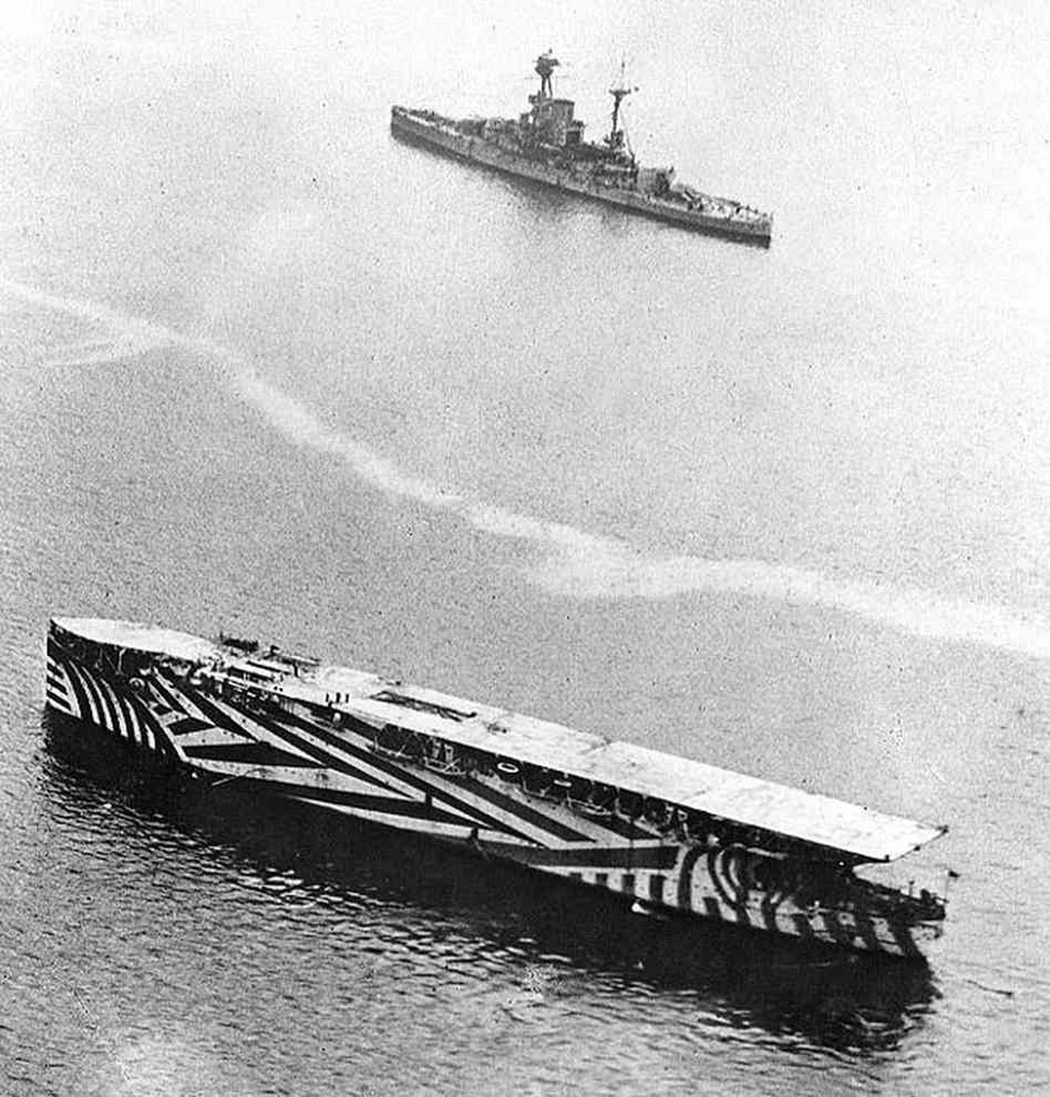

Razzle Dazzle Camouflauge

“Dazzle camouflage, also known as razzle dazzle or dazzle painting, was a family of ship camouflage used extensively in World War I and to a lesser extent in World War II and afterwards. Credited to artist Norman Wilkinson, though with a prior claim by the zoologist John Graham Kerr, it consisted of complex patterns of geometric shapes in contrasting colours, interrupting and intersecting each other.

Unlike some other forms of camouflage, dazzle works not by offering concealment but by making it difficult to estimate a target’s range, speed and heading. Norman Wilkinson explained in 1919 that dazzle was intended more to mislead the enemy as to the correct position to take up than actually to miss his shot when firing.

Dazzle was adopted by the British Admiralty and the U.S. Navy with little evaluation. Each ship’s dazzle pattern was unique to avoid making classes of ships instantly recognisable to the enemy. The result was that a profusion of dazzle schemes was tried, and the evidence for their success was at best mixed. So many factors were involved that it was impossible to determine which were important, and whether any of the colour schemes were effective.”

“At first glance, dazzle seems an unlikely form of camouflage, drawing attention to the ship rather than hiding it, but this technique was developed after Allied navies were unable to develop effective means to hide ships in all weathers.

The British zoologist John Graham Kerr, who first applied dazzle camouflage to British warships in WWI, outlined the principle in a letter to Winston Churchill in 1914 explaining that disruptive camouflage sought to confuse, not to conceal, “It is essential to break up the regularity of outline and this can be easily effected by strongly contrasting shades … a giraffe or zebra or jaguar looks extraordinarily conspicuous in a museum but in nature, especially when moving, is wonderfully difficult to pick up.

While dazzle did not conceal a ship, it made it difficult for the enemy to estimate its type, size, speed, and heading. The idea was to disrupt the visual rangefinders used for naval artillery. Its purpose was confusion rather than concealment. An observer would find it difficult to know exactly whether the stern or the bow was in view; and it would be equally difficult to estimate whether the observed vessel was moving towards or away from the observer’s position.”

“Dazzle’s effectiveness was highly uncertain at the time of the First World War, but it was adopted nonetheless. In 1918, the British Admiralty analysed shipping losses, but was unable to draw clear conclusions; with hindsight, too many factors (choice of colour scheme; size and speed of ships; tactics used) had been varied for it to be possible to determine which factors were significant or which schemes worked best. Thayer did carry out an experiment on dazzle camouflage, but it failed to show any reliable advantage of dazzle over plain paintwork.”

>>Article from Wikipedia. Photography from Twisted Sifter.

>>Article from Wikipedia. Photography from Twisted Sifter.